Jim Bennett, pre-eminent historian of scientific instruments, former Curator of the Whipple Museum, former Fellow and Senior Tutor of Churchill College, internationally celebrated curator and museum director, has died in Oxford at the age of 76.

James Arthur Bennett—always Jim to his friends—was born on 2 April 1947. After an early education at Grosvenor High School, Belfast, he entered Clare College, Cambridge, taking his BA in Natural Sciences in 1969, including the Part II in History and Philosophy of Science (HPS). In 1974 he completed his PhD in the same department under the supervision of Michael Hoskin, subsequently published as The Mathematical Science of Christopher Wren (1982). A year in Aberdeen as a lecturer was followed by an extremely fruitful stint as Archivist of the Royal Astronomical Society, during which Jim systematically sorted and catalogued its immense collection of papers. His resultant catalogue, published in the Society's Memoirs, has been consulted by generations of historians and remains much used to this day. Characteristic of his extraordinary productivity, Jim also found time at the RAS to pursue what would become an abiding interest, producing a series of pathbreaking studies of the reflecting telescopes of William Herschel.

A move to the National Maritime Museum in 1977 confirmed Jim's status as a curator of exceptional talent, cemented two years later by his appointment as successor to David Bryden as Curator of the Whipple Museum in Cambridge. Here he pursued the synthesis that defined his career: wide-ranging research into the material culture of scientific practice, wedded to the mounting of innovative displays, all underpinned by a vibrant teaching programme in HPS. In his Part II course on the history of scientific instruments, Jim taught his students what they came to call 'Bennett's Law': if an object is on display in a museum, then it has probably never been used. This point defines both the inventiveness of Jim's teaching and the potency of his scholarship. If instruments were worth studying, then it was in their use that they held particular value. Working in opposition to dominant modes of intellectual history, Jim studied not only what scientific practitioners wrote, but also what they did. Treating science on the terms of its actors revealed working worlds that were overwhelmingly concerned with the practical means by which one could calculate, scrutinize, navigate, gauge, assay, and measure. This attention to the material culture of practice revealed the deep entanglement of natural philosophy and artisanal labour. So, for example, his ground-breaking 1986 paper 'The Mechanics' Philosophy and the Mechanical Philosophy' offered a strikingly novel account of the fruitful interactions between practical mathematics and natural philosophy in the experimental paradigm of the early Royal Society. And his interventions into debates over the 18th-century 'discovery' of a workable method for determining longitude at sea brilliantly cut through sectarian debates over the primacy of ingenious horologists or theoretical astronomers.

None of this work was done at the expense of texts. Instruments are largely inscrutable when divorced from their conditions of use, and so collections, Jim argued, need to be placed in dialogue with sources capable of revealing those contexts. His genius was in recognising the extremely mixed nature of these sources. Just as the study of working instruments required a shift in focus towards the more mundane objects typically left languishing in museum storage, so a thoroughgoing account of science as practice required a careful study of the myriad vernacular texts typically overlooked by historians of scientific ideas. To give just one example, Jim pointed out that mathematical texts of the European Renaissance are overwhelmingly interested in the art of 'dialling'; yet neither this phenomenon nor its products—the sundials found in museum collections in far greater numbers than optical or philosophical instruments—had then been accounted for within the historiography of a so-called 'scientific revolution'. As was typical of so much of his work, this was an essentially additive intervention rather than merely a censorious one. Jim was genuinely captivated by early-modern mathematical culture, which he always portrayed as lively and inventive and which he wanted to see more widely appreciated. "There is much more to be said about the history of natural knowledge, and of such related technical skills as mathematics," he wrote in 1998, "than can be contained within accounts of discoveries, explanations, ideas, schools of thought, and philosophical argument."

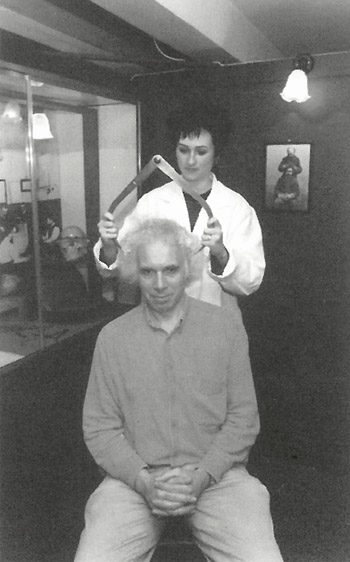

Jim's own appreciation of these practical worlds began with his engagement with collections, and it is here that his legacy meets a parallel and second career, as a curator of extraordinary knowledge and industry. As soon as he joined the Whipple, Jim committed to publishing its collection in order to bring it into full view. Eight catalogues written by him and a range of expert collaborators provided for the first time a clear and systematic account of the major sub-categories of the Museum's holdings (see Appendix B). Alongside this work, Jim curated or co-curated no fewer than seventeen exhibitions whilst in Cambridge (see Appendix A), each with accompanying catalogues and often a programme of public talks or educational posters. These shows were much more than mere rearrangements of the collection. Bringing together Jim's own scholarship with that of colleagues and students, each was designed to link the critical reinterpretation of objects with the generation of new insights into the nature of past scientific practice. Judicious acquisitions established a tradition of growing the Whipple's collection to support exhibitions and research; and because Jim always wanted to get at the use of a thing, displays were often augmented with working replicas. So visitors to Empires of Physics entered into a cluttered laboratory mocked up to evoke the experience of practical bench teaching and research in the early Cavendish Laboratory. And visitors to 1900: The New Age entered via a working replica of H. G. Wells's time machine, which transported its passengers back to the bustling centre of Paris's Exposition Universelle, where they could get their photograph taken and their vital measurements recorded on a carte de visite in the style of Alphonse Bertillon's biometry (see image). A penchant for the theatrical was particularly evident at Christmas, when Jim would dress up as a Victorian magic lanternist and perform a show for the Department using original lanterns and slides from the collection. That Jim also found time to serve as Senior Tutor at Churchill College during this period speaks to his quite extraordinary energy, as well as his commitment to his many students.

Jim being measured in 1900: The New Age

Those privileged to spend time with Jim amongst collections received a model education in the value of curatorial expertise. By the 1980s he had become a preeminent authority on a range of scientific instruments, in particular devices for surveying, navigation, astronomy, and practical mathematics, which he stressed were always best understood in relation to one another. His lavishly illustrated book The Divided Circle (1987) remains the definitive English-language reference work in this area. His Church, State and Astronomy in Ireland: 200 Years of Armagh Observatory (1990) captures his passion for the history of science in Ireland and his unparalleled understanding of the connections between astronomers, institutions, instruments, and their makers. The lucid explanations provided in his Navigation: A Very Short Introduction (2017) brilliantly synthesise a career spent studying and teaching the lived experience of using instruments to find one's place in the world. Jim knew well that all of this scholarship rested upon a foundation of specialist cataloguing, so it is fitting that his final book-length work is the magisterial Catalogue of Surveying and Related Instruments (2022) for the Museo Galileo in Florence.

In 1994, Jim moved to Oxford to succeed Francis Maddison as Director of the Museum of the History of Science. He curated or co-curated a further eighteen exhibitions there, as well as working with his friend and life-long collaborator Stephen Johnston to establish a museum-based Masters course in 'History of Science: Instruments, Museums, Science, Technology', which ran from 1996 to 2006. It is fitting that the 50th anniversary of the British Society for the History of Science, in 1997, afforded him the opportunity to remind both universities of the importance of their museums. That any history of science was taught at these institutions, he pointed out, was a direct consequence of the establishment of major collections there by outside donation. The value gained from activating these collections was a repeated point of emphasis in Jim's many astute essays on museology and the value of science museums. Gains made across this sector since the 1990s owe a great deal to his energy and to his selfless mentoring of a huge number of younger curators and scholars.

A plethora of awards came to Jim in later life: The Paul Bunge Prize of the German Chemical Society, for outstanding contributions to the history of scientific instruments, in 2001; the PhysicsEstoire Prize of the European Physical Society, for achievements in the history of physics, in 2018; the Sarton Medal of the History of Science Society, the highest honour in the discipline, in 2020; and the Royal Astronomical Society's Agnes Mary Clerke Medal in 2023, for his immense contributions to the history of astronomy. Jim was notable for his modesty and so was not one to dwell on the influence of his work. But these awards are a fitting testament to his contributions across museums and historical scholarship—not least his central role in leading our discipline towards a greater interest in material practices. Of course, Jim saw the benefits and challenges of this move earlier than most, and so it is informative to return to his 2002 Presidential Address to the British Society for the History of Science, where he dwells upon "an irony of the current vogue for instrument studies in the history of science", namely, that "historians still make little use of surviving instruments as resources for research." If this is as close as Jim ever got to a manifesto, then it is one that remains quintessentially constructive and focussed on solutions rather than admonishments. In this respect Jim was much like the ingenious practitioners that he studied: unostentatious, thoughtful, and practical to very good effect.

Joshua Nall

Appendix A: Exhibitions curated or co-curated by Jim Bennett at the Whipple Museum

- The Compleat Surveyor, 1982

- Science at the Great Exhibition, 1983

- The Great Telescope of Birr Castle, 1983

- 300 Years Advertising Science, 1983

- The Celebrated Phaenomena of Colours: The Early History of the Spectroscope, 1984

- Science and Profit in 18th-Century London, 1985

- The Grounde of Artes: Mathematical Books of 16th-Century England, 1985

- The Social History of the Microscope, 1986

- Newton's Principia, 1687–1987, 1987

- The Ivory Sundials of Nuremberg, 1500–1700, 1988

- Le Citoyen Lenoir: Scientific Instrument Making in Revolutionary France, 1989

- Rutherford, 1990

- Charles Babbage, 1991

- A Decade of Accessions, 1992

- Empires of Physics, 1993

- 1900: The New Age, 1994

- Sphaera Mundi: Astronomy Books 1478–1600, 1994

Appendix B: Catalogues, exhibition guides, and monographs published by the Whipple Museum, 1979–1994

- Jim Bennett & Olivia Brown, The Compleat Surveyor (1982).

- Olivia Brown, Whipple Museum of the History of Science Catalogue 1: Surveying (1982).

- Olivia Brown, Whipple Museum of the History of Science Catalogue 2: Balances and Weights (1982).

- Jim Bennett, Whipple Museum of the History of Science Catalogue 3: Astronomy and Navigation (1983).

- Olivia Brown, Whipple Museum of the History of Science Catalogue 4: Spheres, Globes, and Orreries (1983).

- Jim Bennett, Science at the Great Exhibition (1983).

- [Jim Bennett], The Great Telescope of Birr Castle (1983).

- Jim Bennett, Whipple Museum of the History of Science Catalogue 5: Spectroscopes, Prisms, and Gratings (1984).

- Jim Bennett, The Celebrated Phaenomena of Colours: The Early History of the Spectroscope (1984).

- Stephen Johnston, Frances Willmoth, & Jim Bennett, The Grounde of Artes: Mathematical Books of 16th-Century England (1985).

- Roy Porter, Simon Schaffer, Jim Bennett, & Olivia Brown, Science and Profit in 18th-Century London (1985).

- Olivia Brown, Whipple Museum of the History of Science Catalogue 7: Microscopes (1986).

- Stella Butler, R. H. Nuttall, & Olivia Brown, The Social History of the Microscope (1986).

- David J. Bryden, Whipple Museum of the History of Science Catalogue 6: Sundials and Related Instruments (1988).

- Penelope Gouk, The Ivory Sundials of Nuremberg, 1500–1700 (1988).

- Jim Bennett, Le Citoyen Lenoir: Scientific Instrument Making in Revolutionary France (1989).

- Anthony Turner, From Pleasure and Profit to Science and Security: Eteinne Lenoir and the Transformation of Precision Instrument-Making in France, 1760–1830 (1989).

- Kenneth Lyall, Whipple Museum of the History of Science Catalogue 8: Electrical and Magnetic Instruments (1991).

- Jim Bennett, A Decade of Accessions: Selected Instruments Acquired by the Whipple Museum of the History of Science between 1980 and 1990 (1992).

- Robert Brain, Going to the Fair: Readings in the Culture of Nineteenth-Century Exhibitions (1993).

- Jim Bennett, Robert Brain, Kate Bycroft, Simon Schaffer, Heinz Otto Sibum, & Richard Staley, Empires of Physics: A Guide to the Exhibition (1993).

- Richard Staley (ed.), The Physics of Empire: Public Lectures (1994).

- Jim Bennett, Robert Brain, Simon Schaffer, Heinz Otto Sibum, & Richard Staley, 1900: The New Age: A Guide to the Exhibition (1994).

- Jim Bennett & Domenico Bertoloni Meli, Sphaera Mundi: Astronomy Books in the Whipple Museum, 1478–1600 (1994).